Relics Read online

Relics

Table of Contents

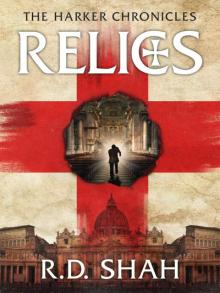

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Acknowledgments

Copyright

The Lost Treasure of the Templars

Relics

R.D. Shah

To Alison for everything

‘I love you more than yesterday but less than tomorrow.’

Chapter 1

‘And that was Fiona Morris with a round-up of today’s headlines here on the BBC World Service. We now return you to our religious correspondent, David Bernstein, for coverage of events live from Rome.’

‘Welcome back to the 267th papal inauguration here in Vatican City, hub of the Roman Catholic faith and focus of over one billion of its followers, on this beautiful January afternoon. I’m reporting to you now from the specially constructed BBC pavilion overlooking St Peter’s Basilica, giving us a bird’s eye view of today’s proceedings. And, as you’d expect, the turnout is immense with an estimated twenty thousand people, all crammed into St Peter’s Square, waiting to get their first glimpse of the new Pope. For those listeners who have just joined us, let me bring you up to speed. It’s been two weeks since the passing of the much beloved Pope Leo XIV, causing wide speculation regarding who will now take up the reins of spiritual power within the Catholic Church. Some have rallied around Cardinal Anitak Onawati of Angola, whose work in Africa has received universal praise from religious and world leaders alike. Another candidate Cardinal Rocca of Germany, described in the media as the “priest’s priest”, has been commended for his good work in the Middle East. It’s, therefore, virtually impossible to predict who will have the number of nominations needed to become Pope, but the cardinals have been in secret enclave behind closed doors for almost forty-eight hours now, deciding who will become the next supreme pontiff. Not an easy job, but about forty-five minutes ago, we saw smoke billowing from the famous chimney on top of St Peter’s Basilica, as the cardinals’ votes were burnt, signalling the end of enclave and the dawn of a new spiritual era. And just a minute ago, we received official word that the decision has indeed been made. And the newly elected Pope is none other than our own British cardinal John Wilcox. What unbelievable news!

‘We’ve had our researchers do a spot of fact checking, and, back in the twelfth century, the first, and the only British pope, was Adrian IV, whose reign lasted just four years, and since then none has followed. Now this, as many viewers will already know, was due largely in part to King Henry VIII, who split the Church of England away from mainstream Catholicism, thus causing a spiritual rift between the old and the new ideologies. But it now seems, after eight hundred years, we’ve finally been forgiven for the disagreements of the past, with today’s elevation of Cardinal John Wilcox to the highest position in Christendom, namely pontiff of Rome.

‘History has been made here today, with the first British Pope in centuries, and this is truly a proud day for … Hold on, I’m getting word that the new Pope is about to make his way on to the famous balcony for his first official address. The doors are still closed, but I’m being told he’ll appear on the balcony any second now. Whilst we’re waiting, I should mention that, because of his liberal thinking, Cardinal Wilcox had been viewed up until now as a long shot. Many churchmen were surprised that he was even promoted to cardinal in the first place, and I’m sure they must be stunned by today’s decision.

‘And back to the action in St Peter’s square, and, do you know, I can’t see a single Union Jack in sight. It seems the decision has caught British Catholics by surprise, too. No, there we go, a few Union flags are now being raised and … I’m getting a message in my earpiece. One of our correspondents on the ground informs me that Cardinal Wilcox has chosen the title of Adrian VII. No doubt a diplomatic choice to appease many within the Church who voiced concerns at an English cardinal becoming Pope, and … Yes, yes, here we go. The balcony doors are opening, and … There he is, our first glimpse of Pope Adrian VII wearing his white inaugural garments and, of course, the unmistakable papal tiara. I don’t know how well you can hear me over the roar of the crowd, but they’re going absolutely wild, and I can see flags of every nation flying high and the cheers. Oh my! I don’t know how well you can make it out at home, but the noise here is deafening. Unbelievable! I must say, it’s hard not to get swept up in the enthusiasm of this event. And I’m not even Catholic!

‘Pope Adrian VII is waving to the crowd with both hands, and they are just as enthusiastic. It seems the politics of his selection is of little importance to this crowd, for they have a new Pope and that’s all that matters. Wonderful! The pontiff is again raising his hands to quieten the people below, but they’re having none of it. I could really do with some earplugs. Wait a minute! That’s odd. Someone has walked on to the adjacent balcony … a man, also wearing a bright white robe. Now he’s pulling himself up on to the parapet and is waving frantically to the crowd. It seems we have an overenthusiastic fan. I reckon someone’s going to get fired for this lapse in security.

‘Oh my God, he jumped! No, he’s still … Oh, this is just horrible. That same man has just hanged himself from the balcony. Everyone’s gone silent, and the security men are bundling the Pope back inside St Peter’s. Please bear with us as we try to find out exactly what’s going on.

‘Hold on, I’m getting word from our man on the ground. Apparently pieces of metal fell from the man’s hands as he jumped. No, wait, I’m being told they’re pieces of silver! Ladies and gentlemen, we’re now going to hand you back to our London studio whilst we try to make some sense of this tragedy. This is David Bernstein reporting live from Rome.

‘Jesus Christ! Paul, that’s fucking horrib … Huh … ? Well, then cut to a break. Will someone please cut to a break?’

Chapter 2

‘And so it gives me great pleasure to introduce to you the man who made this evening’s event possible. His dedication to this area of archaeology is unquestionable, and his knowledge of the subject undeniable.’ Archaeology dean, Thomas Lercher, gripped the sides of the lectern firmly as he addressed the rows of Cambridge alumni sitting attentively before him. The audience consisted of a hand-picked mix of academics and patrons whose pockets were deep enough to make a difference.

The dean took a step backwards, rearranging his ar

ms comfortably behind him.

‘And so allow me to welcome to the stage an outstanding archaeologist, an even better friend, and, most importantly, a member of the Cambridge alumni’ – he craned his head playfully – ‘which means we get him on the cheap.’

Laughter rippled through the auditorium, and, satisfied his joke had gone down well, he threw a hand in the air and gestured to his left.

‘Ladies and gentlemen, I give you Professor Alex Harker.’

Standing at around five foot ten inches, Alex Harker had the slender build of a sportsman. His thick jet-black hair, peppered with grey, was a testament to his years as at thirty-eight, he was about to cross the line into middle age. Dressed in a black tuxedo with polished brogues, he strode confidently over to the speaker’s lectern, where the dean greeted him with a smile from ear to ear. As he took Lercher’s hand and shook it enthusiastically, it was obvious the good dean wanted to milk this moment for all its worth, refusing to loosen his grip until the clapping had totally subsided.

Harker turned back to face the crowd gathered in the auditorium of Trinity College and waited for the applause to fizzle out. ‘Distinguished patrons, associates, ladies, and gentlemen,’ he started, ‘history is a fickle and biased creature. It is written largely by the victorious and then reinterpreted by the generations that follow. As we all know, written history is ambiguous at best, depending on the mindset of the writer at the time and then upon the interpretation we make of it. But I’m willing to wager that, in most cases, it’s never very far from the truth. Of course, embellishment is inherent in human nature, and we know of many monarchs, countries, and battles whose history has been …’ He looked over the audience with a knowing smile. ‘Well, let’s say infiltrated by a few white lies.’ For decades, archaeologists have worked tirelessly to piece together the histories of separate countries and their inhabitants, but in recent years, they have attempted to produce a seamless history of the world at large, and in these efforts, they have done a sterling job. But as archaeology discovers new sites and ever more important evidence, we find ourselves continually rewriting or amending what we already know, and, as we do so, our understanding of the past becomes that much clearer.’

The audience continued to sit patiently, some still as stone, others shuffling in their seats, but it was clear that everyone’s attention was firmly focused on the Cambridge professor as he drew them in further.

‘This is the reason I got into archaeology: to know that your next dig, the next artefact you pull from the ground, could completely rewrite what we know about our past and, in doing so, change our conception of world history.’ Harker paused and smiled at the sea of nodding heads before him. ‘And, more importantly for me, if nothing is found, then you good people wouldn’t be inclined to fund another dig and I’m out of a job.’

Laughter erupted, and he finally felt at ease. Apart from falling off the stage, what could go wrong now, but then a lone voice resonated from deep inside him: Don’t get cocky. It’s not over yet.

‘The truth of our past is something I believe everyone is entitled to share in and to view the objects and texts that make it so. I feel this is a universal birthright, not to be restricted to a select few. So allow me to now introduce you to a piece of history.’

Raising his arm, Harker gestured to the large oak doors on one side of the auditorium. With a creak, they slowly opened and clicked into place, revealing a large rectangular room beyond. Mahogany-panelled walls rose majestically over the black-granite tiles covering the floor, and, as two burly security guards made sure the doors were in place, halogen lights brightly lit up an array of glass-fronted exhibits lining the perimeter.

Dominating the centre of this room was a large display case illuminated from beneath and already flanked by another couple of guards dressed in navy blue uniforms.

‘Ladies and gentlemen, I give you here the largest collection of Dead Sea Scrolls ever to be exhibited in the UK and transported direct from the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.’

Within moments, the crowd was being ushered into the exhibition room. Whispers of excitement passed back and forth as Harker made his way down from the podium and joined the end of the queue. He was confident the speech had gone well, and the audience seemed genuinely engaged. Anyway, he was an archaeologist, not an after-dinner speaker, and the scrolls would now speak for themselves.

* * *

The tabloids had jumped on the story of the British textual archaeologist who had found a collection of rare scrolls in a cave near Damascus, which chronicled daily life around the time of Christ. They included numerous references to the crucifixion and to Jesus’s apostles, which inevitably magnified their significance amongst religious leaders. The tabloids had labelled Harker as Christ’s text keeper, much to his own annoyance, but such exposure had been warmly welcomed by Dean Lercher and his colleagues, even though the majority of his students now referred to him irritatingly as the Text Master.

At the time of this discovery, the Syrian department of antiquities had swooped in on the site and taken the documents off to their own labs for investigation, making it near impossible for Harker to gain access. It had taken over a year to get himself invited to their laboratory, and, after a further six months of testing and restoration, the writings were finally made public and accredited to one Professor Alex Harker.

The writings were not that different in content from the legendary Dead Sea Scrolls, for similar inks and papyrus had been used. The author, presumed to be Jewish, had produced eleven scrolls, written in ancient Hebrew, which described the aspects of daily life in the years immediately before and after the death of Jesus Christ. Harker could still remember the chill of awe that had coursed through his veins on reading those first references to the crucifixion and the beginnings of the Christian religion. These discoveries were hailed by the media as a fantastic insight into the evolution of the Christian faith, but, to Harker, they were primarily another source of knowledge and understanding of what had really happened two thousand years ago. These ancient writings had now given society something factual to depend on in a world rife with religious scepticism. Many of the people who would come flocking to see these texts wanted to find their faith substantiated in writings that had not been diluted and altered over the past two millennia. In an age of science, and freedom of speech, Catholicism had taken a considerable battering. Where faith was once enough, people now demanded fact, and artefacts such as the Damascus texts, as they became known, would give them what they needed – hard evidence.

During one of their first excavations in Jerusalem, the Cambridge team had uncovered a thousand-year-old well. The water itself was long dried up, but the artefacts and clothing surrounding it dated back to around AD 1190. After a year of digging and dusting, they had established conclusively that not only had this well been a major watering hole but it had also been used by Richard the Lionheart and his invading forces during the Third Crusade. Harker had personally found a huge cache of weapons and four iron breastplates bearing the king’s insignia.

He had already begun negotiations with the Israel Antiquities Authority to bring these artefacts back to Great Britain, when a young boy, no older than ten, had walked on to the dig site and asked for the man in charge. When the site manager appeared, the youngster had closed his eyes, murmured a short prayer, and then detonated a half pound of plastic explosive strapped to his chest. The blast was so great the boy’s severed head was later found on a rooftop over a hundred metres away.

Harker had been off site at the time, having spent hours in the Foreign Affairs offices, trying to obtain shipping permits from the commissioner who, frustratingly, had been unavailable most of the day. In fact, it was only when Harker returned to the site in the late afternoon that he became aware of the day’s terrible events.

Twenty people had received moderate injuries, a further five were in a critical condition, and three people were dead. The tragic loss of life was worsened by

the death of his site manager, for Harker’s right-hand man and personal friend, Richard Hydes, had been vaporised instantly. The two men met whilst studying archaeology at Cambridge and had become good friends. When Harker secured his grant for the dig, Hydes had been the first person he called upon for the position of site manager. His old friend jumped at the opportunity, and they had immediately flown together to Tel Aviv to begin applying for visas, work permits, excavation permits, and, of course, religious consent.

The whole process had taken six months, during which time Hydes had fallen in love with a beautiful Israeli interpreter called Mia. The pair had been married just months before the bombing, and it later turned out that the young suicide bomber had been recruited by Hamas’s military branch. Later, there was talk that the attack had been in retaliation for allowing a Jew to work on site, namely Richard Hydes himself.

Unfortunately, the implications had not registered with Harker when he had offered his old friend the position. Archaeologists, like doctors, were usually respected on both sides of the fence and left alone by the extremists. Or so he had thought. Mia had subsequently blamed him entirely for the lack of security surrounding her husband’s death. He had tried to explain that her own government had refused to provide any further security, but this fell upon deaf ears. Her eyes streaming with tears, the recently married Mrs Hydes had thrown him out of the house and even cursed his name. At that moment, he made himself a promise and stuck to it like gospel: always hire locals and never hire a Jew when operating in the Muslim world.

Present in the room this evening was the man who had helped see him through the crisis and who had been site manager on every dig he had undertaken since. Hussain Attasi, or Huss as he liked to be called, had been working as a digger at the ancient well site in Damascus and was injured in the same explosion that had killed Richard Hydes. It was Huss that had taken charge of the site within minutes of the blast and had organised the initial clean-up. Harker could still see the image of Huss clearly in his mind – the nineteen-year-old’s white shirt sprayed red with blood and his face smeared black with bomb residue as he stood arguing with the Israeli military.

Relics

Relics